‘Art and life – there is no separation between the two,” Oscar Murillo says. It is a line that stays in the mind although it is thrown out casually, part of a longer conversation. What is clear is that Murillo’s life is jammed with work to the point where art and life have become almost indistinguishable. He has a solo exhibition, Violent Amnesia (his first in the UK since 2013), at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge; there is a show at David Zwirner’s London gallery; he is reviving a show in Berlin; and, later this month, a further show will open at The Shed in New York.

Murillo is also on this year’s Turner prize shortlist, saluted by the jury for the way he “pushes the boundaries of materials” – especially in his paintings. In addition, he has been commissioned to do a piece for Art Night in Walthamstow, part of the mayor of London’s first London Borough of Culture celebrations in Waltham Forest.

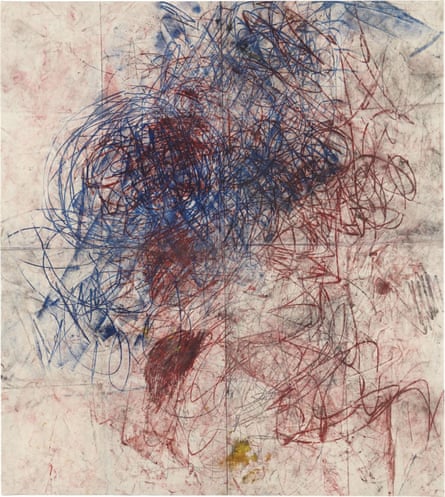

It is a sunny morning, and Murillo arrives late at his Tottenham studio on a bicycle, pleading “the school run” and opening the door to a high-ceilinged, handsome space – several rooms – in which the first thing one notices is a lifesize ragdoll lying on its back like the victim of a crime scene (about these figures, more later). On the opposite wall are two imposing floor-to-ceiling oils in red, black and blue. His paintings are workouts – part of a series called Catalyst – with a fevered cross-hatching of lines.

Their colours carry across the room like voices that cannot be ignored, seeming still to contain the energy with which they were produced. It is only when you look close up that you see the mix of materials: cotton, linen and funereal velvet. He talks about the work as “mark making”. He says it is “therapeutic”. There is no mistaking its instinctive brilliance. Nor is it difficult to imagine how it was that, about seven years ago, while still doing an MA at the Royal College of Art in his early 20s, he was “discovered”.

Success is a mix of luck and talent – Murillo has both, and his rise has been meteoric. He became – thanks, in part, to Donald and Mera Rubell, the Miami-based collectors of contemporary art – an art world phenomenon. In 2013, at Phillips auction house in New York, one of his paintings was estimated at $30,000, and fetched $401,000. But there can be a downside to over-exposure, and from some quarters the critical sour grapes cannot have been easy for a young man (he is now 33).

Murillo has such a gravity of expression that his smile comes as a relief. There is a combative defensiveness, too, mixed up with his generosity. His black jacket is zipped up to the collar on this warm day. He wears a single earring, and his hair is on the edge of exclamatory. He is, unmistakably, a Londoner in his cool garb and yet – for ever – a Colombian. The connection becomes clear on arrival, as he brews an espresso. Generously, he offers me, as a present, a packet of coffee – Valle del Cauca, Roldanillo, from western Colombia, where he was born in a small town called La Paila. He searches his phone for an image of the breathtakingly beautiful blue-green valley where the coffee was grown. A tiny image, so far from Tottenham. We exclaim over it and sit down to talk.

There is in Murillo’s work a disturbance, a drama, a sense that paint itself is on the move – this is the defining effect of the Kettle’s Yard show. And yet the work is arresting in the fullest sense: you are stopped in your tracks by a blackened canvas hanging in your way like a chaotic garment, part brick-shaped patchwork, part frenzied scribble. Beyond, is a bold, ongoing installation called The Institute of Reconciliation. The floor is covered in black, cast-off canvases – sails turning into a sea. These have been hurled by Murillo against the gallery’s white wall, which is now covered in black smudges like the whispered memory of a fight.

Over the road, in tiny St Peter’s church, there is an astonishing congregation of Murillo’s stricken, papier-mache-faced models (in Colombia, they burn effigies – usually of politicians – at New Year). These ordinary folk sit in pews (purchased from a defunct church in Greenwich) that have been attacked by Murillo with an axe. They seem to await an explanation.

He has always been a versatile artist (painting, video, sound works and performances) and with a particularly authoritative sense of theatre. His most famous piece was his 2014 recreation of a factory from his home town, called A Mercantile Novel, complete with Colombian workers who brought their production line of chocolate-covered marshmallows to David Zwirner’s gallery in New York. Some critics thought Oscar and the chocolate factory gimmicky, but no one could deny his daring.

I decide to risk the million-dollar question: how does he define art? He is a nomadic conversationalist, confessing that his talk is as “curving” as a mountain road – in a Colombian landscape, maybe.

“There are two parallel answers to this question,” he says. “It’s important to be aware of art history. I went to Westminster University, where there was an incredible history of art tutor. This set the tone for my career. We went through art history chronologically. You consider how art interacts with science, politics and religion. As an 18-year-old, you begin to understand the marriage between art and life. You compare historical patronage with the contemporary context.”

Art history gave him a “compass” and a “permission” and a “confidence” to do his own thing.

“But history is history and you think: now let me forge my own path, ignoring what is allowed or not allowed… just going for it.”

Asked how he feels about being on the Turner prize shortlist, he is reluctant to expand.

“Art is an echo chamber and artists are often in a little bubble.” The Turner prize is valuable as a “vessel of discourse”. But is he stressed about it? “Not at all.”

“Just going for it” means incessant work. He describes himself as a “restless spirit” for whom migration is a problematic subject. He has a way of anticipating difficult conversations before they have materialised: “I’m not interested in a conversation about migration in relation to me; my work does not come from that,” he warns.

What’s more, migration has a tendency to overpower: “It can be too easy to say that being a migrant is a key to identity.”

Murillo came to Hackney, east London, from Colombia at a time of economic meltdown in his country. He was 10 and spoke no English at all – which he has described as “confusing.”

In the Kettle’s Yard show, there is an extraordinary sound piece called My Name Is Belisario, narrated by Murillo’s father in Spanish, about migrating to the UK, which is translated into English, French, German, Hebrew and Arabic. You tune into this babel discontinuously, experiencing his father’s dislocation vicariously through sound.

“Like many people throughout history, my father took a decision rooted in desperation, curiosity and desire that radically changed the course of our family’s history. A lot of my improvisation is rooted in my father’s will as a human being, his restlessness, his desire to go beyond his limited existence.”

His father looked at London on a world map and asked himself: “Why not try it over there in that country?” It is moving to learn that he wept all the way from Colombia to London on the plane – distraught at leaving family behind.

Does Murillo think about how different his own life might have been had his father not taken the radical decision to come to the UK?

“Of course… I think about it constantly. I’d most likely have been working in a factory [the marshmallow factory, presumably]. There is a 70% chance that would have been the case.”

And where is home emotionally – Tottenham? Colombia?

“Colombia is an incredibly racist and hypocritical country with a quasi-apartheid system. I have this repetitive, waking dream of being in a large water tank, pitch-black. Someone is submerging the top of my head, oppressing me, holding me down, and I have only a little oxygen left. They pull me back up until I’m conscious and able to continue with existence. That is what Colombia is like. The oxygen is the beautiful landscape I just showed you. It’s that beauty in nature that keeps people in Colombia alive. People have this existence of – you name it – corruption, racism, oppression. I’m not going to romanticise it at all. It is a terrible country.”

He goes back there often, he says.

It is easy to present Murillo’s life as an over-simplified rags-to-riches story – to emphasise that he was working as a cleaner in the Gherkin building in the City when he first made a name for himself (the Gherkin, in this Cinderella-esque context, ought to have been a pumpkin). But this take on his story nettles him, because the reality was other – he was a teaching assistant before becoming a cleaner: “The story of me as a cleaner is more sensational than the story of me as a teaching assistant in schools – trying to forge a career as an artist.”

It was during the school holidays, he explains, when he was able to work full-time as an artist, that “the penny dropped”. He saw he needed more time for his art.

“My priority had never been the teaching – that was just a really sad way of making money. But if you think about cleaning, it’s a beautiful thing, because the only sacrifice you have to make is to wake up pretty early [laughs]. When I worked in the Gherkin, I’d wake up at four in the morning – which in the summer was perfect because it is already daylight – and I’d cycle from Dalston to Liverpool Street, a really nice cycle ride, and see busloads of migrants going to the city. And then I’d get there and there’d be nobody there. How much dirt can an office worker produce? It’s very minimal. And then, from 9 o’clock until I was really tired, I could go on working [on his art] – my entire day was free.”

And when it was no longer financially necessary to work as a cleaner (people used to talk about “the Murillo effect” when discussing the art market), was there any pressure in finding himself suddenly wealthy and conspicuous?

“What do you mean? Where is the peril? What is the concern? When you have an Instagram or Facebook account, most people show the best of themselves, a false profile. Beautiful selfies, holiday pictures, nice hotels. Yet when you meet that person, you’ll know that is far from the truth; they have a very normal existence, even if they have made it big. The content of my work is social investigation and collaborative. It has been embedded in social discourse for as long as I can remember, and focused on family life. That’s what matters. You are never going to catch me living a life of lavishness, because that is not interesting. And if working with a successful commercial gallery and selling my work means an income, then that is shared among the people I love – my extended family and friends.”

There is no overstating the importance of family to Murillo.

“I’m interested in the wellbeing family brings,” he says. “That I can have the people I care about round me is a huge virtue.”

He has two young daughters and tells me he is determined not to steer his children in an artistic direction – it matters to him that they find their own path.

“My eldest daughter, Valentina, who is nine years old, has an innate interest in art; and once, when we were in New York where I was doing a residency, at two years old she got completely covered in paint – I have the picture of her burnt in my memory… a beautiful sight. But pushing kids towards art because I’m an artist? No, I do not want to impose myself.”

His family are to be an important part of Walthamstow’s Art Night. He is inviting more than 30 family members and friends to take part. “I’m going to sign them up as members,” he says.

Walthamstow Trades Hall is a club for working people. Murillo tells me in advance that it’s a sense of the time warp that inspires him when visiting the place: “Gentrification has involved social destruction, but walking into this members’ club is like walking 30 or 40 years back in time. It gives you an understanding of a society that has become marginalised.”

The building looks as if it has worked and partied hard for decades. The letters on its front door are like a few teeth hanging on in an old man’s mouth. T AM OW TR DES A. The club was established in 1920 and now has more than 200 members, with a core group of elderly people (membership £35 per year). Loyal club member Brenda Shearing, who has been on the committee for 17 years, shows me round and says she hopes the club will “go on for ever”.

Clubs like this are closing down across the UK, and Murillo’s intervention will, they hope, encourage a younger membership – people who want to commit time and TLC to the place. In a later phone call, Murillo talks about “long-term commitment… I don’t want Art Night simply to be a gesture”. Helen Nisbet, artistic director of the event, suggests that his family and friends will bring “a new conversation and culture” to the place. And his family’s membership money will contribute to the club’s future.

Visitors to Art Night can look forward to bingo, live music and a large dance floor. In the 70s and 80s, dancers used to queue round the block to get in. And on 22 June, Cathy, one of the club’s oldest members, will celebrate her 90th birthday here, with a line-up of crooners. She has been informed about Murillo’s performance – she was offered the option to celebrate her birthday on another night, but is staying put. Besides, Murillo will not disturb her, as he is to perform outside. His inspiration will be the 1987 Proclaimers song Letter from America (sung a cappella).

I spent the evening thinking about

All the blood that flowed away

Across the ocean to the second chance

I wonder how it got on

When it reached the promised land?

These powerful lyrics are about people affected by the destruction of industry in the Scottish lowlands in the 1980s, and look back to the 18th-and 19th-century Highland Clearances. There is no puzzle about why they should speak to Murillo or to any migrant who has ever searched for a promised land.

In 2016, Murillo famously tore up his British passport (he also had a Colombian one) and flushed it down the toilet of a plane en route to Sydney (he was detained in Sydney, deported to Singapore, eventually returned to Britain). And there is no mistaking his vitriol when he says he wishes to “hold a mirror up to this country, which is culpable of waves of migration – including the Irish and Scots leaving their homelands because of persecution and having to go to America. There is still a notion that western society somehow occupies a higher moral ground. The discussion about ethnicity needs to be reversed.”

The Trades Hall has further concentrated Murillo’s mind on what he describes as “the tragic hypocrisy of the British people …This country has no concern for the working people. It happens in the context of art too. You can talk about race all you like, and yet there is no comparable conversation about class. Yet class touches the core – it is a raw wound. You have people who live below the poverty line on this island.”

The outrage in Murillo is tangled up in melancholy. In a leaflet accompanying the Kettle’s Yard show, he remembers taking a bullet train in Tokyo, in 2017, and encountering a Japanese phrase, “Mono no aware”, which translates as “the pathos of things”. He has suggested that this inspired some of the work in his show. Yet the last thing he tells me – offered as an over-arching thought – is more about people than things. He says what concerns him most, in all his work, is “the loss of humanity within our society, whether in my family or other communities”. And you can hear, even in his tone of voice, that for Murillo, lamentation is always on the edge of revolt.

Art Night is on 22 June in Walthamstow and King’s Cross, London. Oscar Murillo: Violent Amnesia is at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, until 23 June; Manifestation is at David Zwirner, London W1, until 26 July

Art Night 2019: other highlights

Transforming car parks, malls, a market and more, the fourth edition of Art Night comprises more than 50 projects taking place on 22 June in Walthamstow and King’s Cross. Alongside Murillo’s work, highlights include:

The first outdoor commission in the UK for over 15 years by veteran US artist Barbara Kruger. The large-scale work, Untitled (look like us, talk like us, think like us, pray like us, love like us), will be in Walthamstow Town Square.

New Yorker Cory Arcangel (who studied classical guitar before turning to art) collaborates with organist Hampus Lindwall for They told me there would be tea in which leading artists have composed new music for the organ of St Mary’s church, Walthamstow. Meanwhile, in the more workaday venue of Sainsbury’s car park, Joe Namy will create a sound installation using cars (The Eighth Automobile) and, along Walthamstow market, British duo Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings will present a musical spectacle exploring gay culture.

In King’s Cross, Marina Abramovic fans should seek out the UK premiere of her first virtual reality piece, Rising, while Coal Drops Yard will host US sound artist Christine Sun Kim, who has collaborated with students at Frank Barnes School for Deaf Children for We Mean Business, a three-part commission exploring deafness. Imogen Carter